|

2

2

-

2 Immagine

tratta dal Digital

Lunar Orbiter Photographic Atlas of the Moon:

In questa immagine si può ammirare la bella struttura concentrica di

Hesiodus-A.

-

2

Image by Digital

Lunar Orbiter Photographic Atlas of the Moon:

In this image we can admire the intersting concentric structure of

Hesiodus-A.

3

3

-

3 Immagine

tratta dal Digital

Lunar Orbiter Photographic Atlas of the Moon:

In questa immagine si può ammirare la bella struttura concentrica di

Marth.

-

3

Image by Digital

Lunar Orbiter Photographic Atlas of the Moon:

In this image we can admire the intersting concentric structure of

Marth.

4

4

-

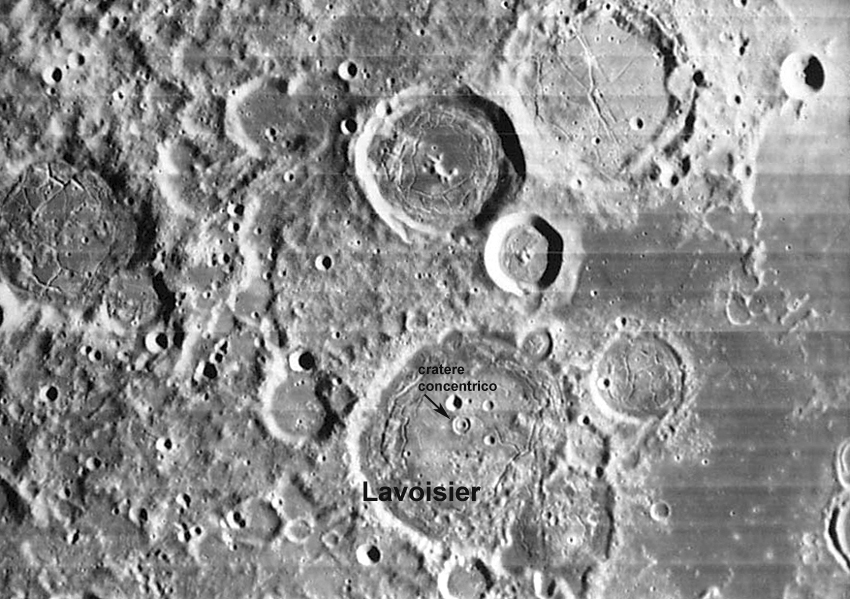

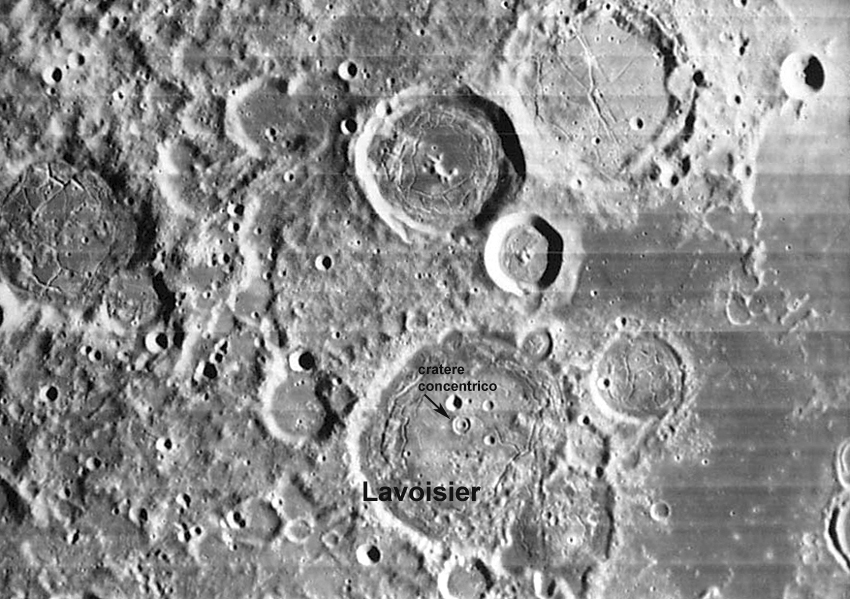

4 Immagine

tratta dal Digital

Lunar Orbiter Photographic Atlas of the Moon:

In questa immagine si può ammirare la struttura concentrica in

prossimità del centro della platea del cratere Lavoisier.

-

4

Image by Digital

Lunar Orbiter Photographic Atlas of the Moon:

In this image we can admire the intersting concentric structure

inside in Lavoisier crater.

In tutti i corpi

solidi del nostro sistema solare è stata ormai accertata la presenza di

numerosissime strutture crateriformi aventi le più svariate dimensioni,

la cui formazione è da far risalire all’epoca in cui grandi impatti

meteoritici ne sconvolsero ripetutamente le superfici. Pertanto anche la

nostra Luna fu costretta a subire lo stesso tumultuoso trattamento, ed

il risultato è quello che ormai da oltre quattro secoli (anche se

personalmente credo da epoche ben più remote…..) possiamo

dettagliatamente osservare con i nostri telescopi sempre più

perfezionati. Mentre la comune tipologia di un cratere da impatto è

costituita da una struttura circolare contornata da pareti più o meno

elevate e dalla frequente presenza di un sistema montuoso centrale, vi

sono crateri la cui particolare morfologia potrebbe accreditarne una

differente origine: si tratta dei crateri concentrici. Ufficialmente

sono 51 le strutture attualmente conosciute appartenenti a questa

anomala tipologia di crateri distribuiti sulla superficie lunare.

Tra le principali

caratteristiche vi è il diametro, mediamente di circa 8 chilometri, con

la platea contenente anelli concentrici. Questi anelli circolari interni

possono essere costituiti da deboli corrugamenti più o meno degradati

(crateri più antichi) oppure con rilievi netti e ripidi, come terrapieni

relativamente appiattiti oppure con una sorta di collare concentrico

intorno alle pareti esterne. Con un diametro di 15 chilometri Hesiodus-A

rappresenta il tipico esempio di cratere concentrico. Questo si trova

sul lato meridionale del mare Nubium immediatamente a sudovest di

Hesiodus. Da immagini del Lunar Orbiter l’anello più esterno sembra in

ottimo stato di conservazione, mentre quello interno presenta alcune

irregolarità lungo la parete rivolta all’esterno. In posizione centrale

si nota ciò che potrebbe sembrare quanto rimane di un piccolo craterino.

Secondo alcuni osservatori, la pendenza esterna degli anelli concentrici

sarebbe convessa, mentre in un normale cratere da impatto questa risulta

essere concava. L’anello esterno di Hesiodus-A sarebbe alto circa 1700

metri, un valore pari al 55% di un normale cratere avente lo stesso

diametro, mentre l’anello interno avrebbe un’altezza pari al 45% della

profondità del cratere principale.

Circa l’80% dei

crateri concentrici oggi conosciuti è distribuito lungo le zone

marginali di confine tra le pianure e gli altipiani, mentre ne viene

esclusa la presenza al centro delle più vaste aree pianeggianti. Un

ulteriore 20% circa si trova all’interno di grandi strutture

crateriformi inondate di materiale lavico, frequentemente in prossimità

di fatturazioni della crosta superficiale. Esiste un criterio di

classificazione di queste particolari strutture, in base al quale viene

assegnato un valore da 1 (se in buono stato di conservazione) a 5 (se

degradato), inoltre M: pianura – C: altipiano. Volendo considerare solo

i 16 crateri concentrici più noti sul totale di 51 attualmente

conosciuti appartenenti a questa tipologia, appare subito evidente come

questi siano in gran parte localizzati nelle aree pianeggianti mentre

solo alcuni sono situati sugli altipiani sudoccidentale e sudorientale.

Iniziamo il nostro

viaggio fra i crateri concentrici presi in esame partendo dal mare

Frigoris, con Archytas-G e Fontenelle-D rispettivamente di 7 e 17

chilometri di diametro entrambi di classe 2M, con anelli interni poco

visibili ma in buono stato di conservazione. Lungo il bordo occidentale

del mare Imbrium, Gruithuisen-K di classe 2MC, diametro di 6 chilometri,

dove alcuni osservatori hanno potuto osservare sullo strato di ejecta

tre piccoli crateri concentrici con anelli interni ormai degradati.

Passando all’oceanus Procellarum, 50 chilometri ad ovest di Markov

(diametro 43 km – pareti di 2450 metri) si può osservare un piccolo

cratere concentrico di 7 chilometri, classe 3M, con anello interno in

buone condizioni mentre la parete esterna si presenta parzialmente

degradata. Circa 230 chilometri ad ovest di Markov, nei pressi di

Repsold in una zona percorsa dall’interessantissima ragnatela di solchi formata

dalle omonime rime vi è Repsold-A, classe 1C, diametro di 9 chilometri

con struttura concentrica in ottimo stato di conservazione. Scendendo

più a sud nell’area di Lavosier, diametro 71 chilometri e pareti alte

2000 metri, abbiamo alcuni crateri concentrici di cui il primo, con

diametro di 6 chilometri, all’interno dello stesso cratere principale in

posizione centrale mentre il secondo, non ancora definitivamente

riconosciuto come tale e di soli 3 chilometri, viene indicato nei pressi

di Lavoisier-A. Secondo il parere di chi scrive anche Lavoisier-T,

diametro di 19 chilometri, presenta una struttura almeno apparentemente

concentrica con anelli interni ben conservati. Sempre nell’oceanus

Procellarum passiamo ora alla platea di Struve, un grande cratere di 175

chilometri dove una struttura concentrica di circa 6 chilometri, classe

2MC con debole anello interno, è individuabile vicinissimo ad un altro

cratere dello stesso diametro disposti in senso nord/sud. Abbandonato l’oceanus

Procellarum, nei pressi di Cruger (diametro di 48 chilometri) viene

segnalata la presenza di un piccolo cratere concentrico con diametro di

soli 2,5 chilometri di classe 3C, ubicato in pieno altipiano di

sudovest. Sempre in questo vastissimo altipiano ma circa 500 chilometri

più a sud la bella struttura concentrica di Lagrange-T di 12 chilometri

e di classe 2C, con un secondo cratere concentrico di 9 chilometri poco

più a sud e di classe 4C, quindi molto più degradato. Spostandoci verso

il margine ovest del mare Humorum, nella platea di Mersenius (diametro

di 87 chilometri) abbiamo in posizione decentrata verso est la struttura

concentrica di Mersenius-M di soli 5 chilometri di diametro e di classe

2M. Nella vicina Palus Epidemiarum uno dei più interessanti esempi di

cratere concentrico è costituito da Marth, classe 2M, diametro di 7

chilometri e con anelli concentrici ben conservati aventi forma

lievemente ellittica in senso nw-se. A sud della Palus Epidemiarum, sul

margine del grande altipiano meridionale, la struttura concentrica di

Hainzel-H, diametro di 11 chilometri e classe 3C, si presenta con

l’anello interno piuttosto degradato. Per andare alla ricerca della

struttura concentrica di Hesiodus-A dobbiamo spostarci sul lato

meridionale del mare Nubium, immediatamente a sudovest di Hesiodus (44

chilometri). Questo cratere concentrico, in ottimo stato di

conservazione, è di classe 1M e con diametro di 15 chilometri. Nella

parte sudorientale del mare Fecounditatis, fra i crateri Crozier e

McClure, Crozier-H è un altro esempio di cratere concentrico con anello

interno di forma ellittica, con diametro di 11 chilometri e di classe

2C. Infine, in pieno altipiano sudorientale fra i crateri Pontanus ed

Azophi, la struttura parzialmente degradata di Pontanus-E, diametro di

13 chilometri e classe 3C.

Nella stragrande

maggioranza delle strutture lunari sono presenti crateri minori, quale

logica conseguenza di impatti verificatisi successivamente rispetto

all’evento originario, ma si ritiene altamente improbabile che

all’origine di questa particolare tipologia di crateri (concentrici) vi

sia esclusivamente la caduta al suolo di corpi meteoritici,

indipendentemente dalla dinamica dell’impatto stesso. Vi sono inoltre

strutture, non propriamente appartenenti a questa tipologia, che nella

loro platea contengono più anelli circolari interni, tra cui Sabine,

Ritter, Vitello, Posidonius, Gassendi ed altri, con diametro nettamente

maggiore rispetto alla media di circa 8 chilometri tipica dei crateri

concentrici. Si possono citare macro strutture come, ad esempio, il mare

Orientale, costituito da enormi anelli montuosi concentrici generati

dall’onda d’urto in seguito all’impatto, la cui genesi però ha ben poco

a che vedere con la tipologia esaminata in questo articolo.

Se è vero che, fino a

prova contraria, la semplice caduta di un corpo meteoritico non può

generare strutture concentriche come quelle viste più sopra, allora non

potremo esimerci dal considerare l’attività vulcanica del nostro

satellite, spostando la nostra attenzione verso i domi lunari.

All'epoca dei grandi impatti

meteoritici, la conseguente frantumazione di parte della crosta provocò

la fuoriuscita di materiale lavico il quale si riversò in superficie.

L'attività vulcanica lunare si manifestò anche con eventi non

necessariamente così catastrofici, ma anche attraverso i domi, antichi

edifici vulcanici sulla cui sommità in passato vi doveva essere

l'apertura della bocca eruttiva, colmata dal magma fino a modellare il

domo nella forma in cui lo vediamo oggi. Inoltre vi è una seconda

ipotesi basata sul fatto che l'attività vulcanica lunare non si

manifestò solamente nel modo violento ed esplosivo così come la

conosciamo sul nostro pianeta, ma per formare tali strutture la

fuoriuscita di materiale lavico deve essere avvenuta in modo molto meno

violento: solo così la lava può riuscire a colmare una bocca eruttiva

(o parte di essa) per poi scendere ed accumularsi lungo il pendio del

domo.

Ora si tratta di

andare alla ricerca della eventuale correlazione fra strutture

crateriformi concentriche

ed antichi coni vulcanici, ma questo richiederà una notevole pianificazione di

osservazioni sistematiche e dettagliate di questi crateri, oltre

all'analisi approfondita di tutta una serie di dati acquisiti in un arco

di tempo certamente non breve. Molto probabilmente ci troviamo

di fronte a strutture che, essendo state testimoni del manifestarsi di

varie forme di vulcanesimo hanno probabilmente costituito un ruolo

importante per quanto concerne la storia geologica e la formazione delle pianure e degli altipiani della nostra

Luna. |

1

1